The following headline in FT “Negative-yield debt breaks $10tn level for first time”, got us thinking on the investment implications of living in a world where people are happy to take a loss to keep their capital safe with sovereigns. A lot of observers are quick to blame central banks orthodox policies for the current state of affairs, ignoring the fact that bankers are reacting to an economic environment and are not the sole drivers of economic activity.

As Mario Draghi, the ECB president enunciated in a recent speech, addressing causes of low interest rate, Quantitative Easing (QE) and low rates are not a problem but a symptom of an underlying problem, the lack of investment opportunities to absorb excessive savings. Nearly a quarter of world economic output is today generated in regions subject to deflationary forces, with negative to low interest rates.

It is not just sovereigns, but also corporates who have started seeing rates turn negative on their debt. This provides a classic dilemma to business managers (of large entities like General Electric, Unilever), if investors are giving them money for free what should they do, take it and invest more or turn cautious, worried about the risk of demand in a deflationary world environment.

The US market provides a good reference point on what is happening in the real world. Instead of using the free cash to invest, managers are borrowing and paying back investors more than what their business are earnings, giving the impression that corporates are not confident of re-investing in their business, as shown by the accompanying chart from a Reuters article with the heading “The Cannibalized company“.

The concept of negative rates, economically, is to provide incentive to banks, financial institutions and savers to move assets from safe bonds to higher yielding activities, which can be viewed as compensation provided for taking the risk of engaging in longer duration investment activity, thereby giving a boost to economic activity and correcting the ‘investment-saving imbalance’ in a large part of global economy. As the above chart highlights, in practise , that is not the case.

The worry on the other hand is that it channels capital to unintended areas resulting in creation of asset bubbles, pricking of which leads to destabilizing boom bust cycles. A more practical issue highlighted by former fed chairman, Ben Bernanke is the risk of people moving towards hoarding currency.

Listening to a press conference by Mr. Draghi this week, we were struck by the defence of recent ECB decision to withdraw €500 notes and replace it with more than adequate quantity of €200 notes. In a world driven by technological innovation, resulting in rapid adoption of electronic payment systems, the defence of paper money looked anachronistic. Reason for this unusual defence was worry among a section of North European savers that central banks are forcing out paper money so that they can easily devalue savings through negative interest rates to tackle European debt problem. Not just individuals, even some institutions are finding ‘cash in a pillow’ option attractive.

Is a low or negative interest environment really that big a deal ?

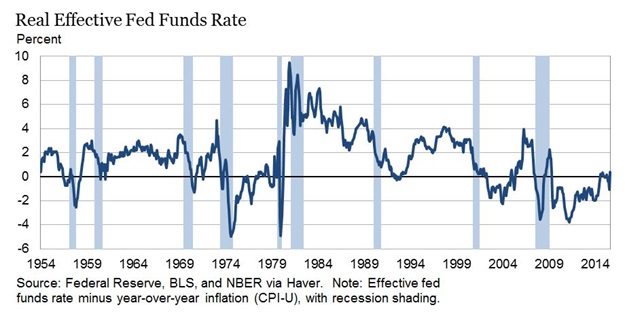

While negative interest rates optically look low, many economists will argue that it is real rates (rates relative to inflation) which matter and not the absolute level of nominal rates. Economic activity is impacted by real rates and not nominal rates.  The above chart of nominal US federal funds rate gives the impression that interest rates are abnormally low by historic standards and recent trend of close to zero rate is an anomaly. But what this misses out is the fact that the rate environment is driven by inflationary expectations. If one overlays inflation on this chart and looks at real rates,

The above chart of nominal US federal funds rate gives the impression that interest rates are abnormally low by historic standards and recent trend of close to zero rate is an anomaly. But what this misses out is the fact that the rate environment is driven by inflationary expectations. If one overlays inflation on this chart and looks at real rates,  the picture looks very different. Over the long run real rates (nominal minus inflation) has averaged about 2% and while rates have been low in recent years, they are not abnormally low.

the picture looks very different. Over the long run real rates (nominal minus inflation) has averaged about 2% and while rates have been low in recent years, they are not abnormally low.

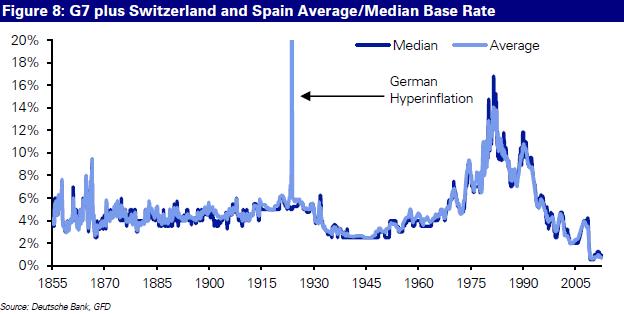

Having looked at the inflation / interest rates trade off, let us go back in time and look at long run trends. The chart below shows the Average and Median short term rates in G7 countries over the last 150 odd years. What is striking is the low and stable rates which

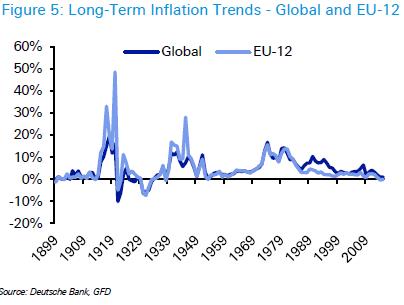

existed for long periods of time. The exception was the period around 1970-80 where geo-politics and oil shock sent world inflation expectations reeling, resulting in the Volcker era of high real rates, brought on to tame inflation. The next chart on long-term trends in inflation highlight the short periods when inflation trends were high. These centred around exceptional events – the two world wars and the oil shock. If one strips these periods out, the conclusion would be that long term inflation trends are generally low and benign. For a generation brought up in the era of oil-shock and high inflation, the current phase of low inflation and interest rate seems an anomaly, but history tells us, except for periods of extraneous shocks, low and stable interest rates are the norm.

existed for long periods of time. The exception was the period around 1970-80 where geo-politics and oil shock sent world inflation expectations reeling, resulting in the Volcker era of high real rates, brought on to tame inflation. The next chart on long-term trends in inflation highlight the short periods when inflation trends were high. These centred around exceptional events – the two world wars and the oil shock. If one strips these periods out, the conclusion would be that long term inflation trends are generally low and benign. For a generation brought up in the era of oil-shock and high inflation, the current phase of low inflation and interest rate seems an anomaly, but history tells us, except for periods of extraneous shocks, low and stable interest rates are the norm.

The problem in financial markets is the perception that QE is the only game in town. As Mr. Draghi has repeatedly stated (in 2014 & 2016), central banks “cannot single-handedly create the conditions for a sustainable recovery in growth”. As OECD urged in its 2016 outlook report, Fiscal policies & Investment incentives in major economics need to become more growth friendly as monetary policy on its own cannot work.

How does negative interest rate policy (NIRP) impact investment opportunities ?

While the investment community is still trying to get to grips with a world of negative interest rates, the one clear impact of NIRP is on financial institutions.

Financial companies business model depends on taking duration risk and getting compensated for it through higher rates. The accompanying chart shows how margins for US banks have been on a steady decline, since the start of QE. A similar impact has been seen in Japan though the experience in Europe has been mixed. The other big impact is on insurance and pension companies who have long duration liabilities which are serviced out of investment income. A lot of pension funds in Western world have an implicit return expectation in the high single digit. In an environment of negative rates some of these plans will be running significant return shortfalls with implication for corporates which have promised defined benefits and for individuals whose retirement comfort depends on income generated.

Some companies are starting to come to grips with this environment, as evidenced by Shell, which enunciated a new strategy for the ‘lower forever’, environment -that is virtually permanently low inflation, low demand, and low interest rates. Business models which can thrive in this new paradigm will be well rewarded by investors.

The starting point for investors thinking about returns in this environment is to lower nominal expectations. What should matter for investors is real return, i.e. returns achieved on capital on top of inflation expectations. In a deflationary world, the nominal returns needed to achieve positive real rates is in the low single digit not double digits. Secondly, one needs to remember the basic fundamental premise, returns offered in financial markets are a reward to compensate for taking additional risk. In a world of uncertainty, with low growth, volatility is likely to be higher. Risk, as commonly measured in financial markets using volatility is not a predictor of returns, it just highlights the near term riskiness of making a loss or gain. Thirdly, history shows us that best returns are achieved by investing in assets where there is excessive pessimism (or in financial terms risk premiums are high). Recent experience since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) would support that. While consensus jumped into Emerging markets in 2009-10 enamoured by growth, the best returns over the five year period 2011-2015 were achieved by being invested in US Equities (S&P 500 +72%) and not MSCI EM (-26%). While developed markets are now facing deflationary challenges, emerging markets have been roiled by commodity collapse and currency volatility, elevating risk premiums significantly, thereby providing good future return opportunities.

At the current juncture, given where valuations and expected risk adjusted returns are, European & some EM equities look lot more attractive than US market, as risk premiums have reached levels where risk adjusted returns are looking attractive. We found a recent article in Valuewalk which drew on work done by Research Affiliates to show the best real expected returns and risk for various asset classes, the conclusions, seemingly in line with our view on where the best investment opportunities are.

[…] Economies in the U.S. and Europe had to resort to unorthodox monetary policies – cutting real interest rates to negative – and to Quantitative Easing. In contrast to the bleak picture in the western world, Asia, […]

LikeLike

[…] is true is the fact that we have been living in an extra-ordinary period of monetary easing with lower than normal rates for the last decade, a period where profit growth has been skewed towards a narrow winner takes all […]

LikeLike

[…] is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”. After a couple of decades of stable inflation (lower for longer), the simultaneous monetary stimulus unleashed by major central banks of large economies (the US, […]

LikeLike